History of Dog Sports

From time to time, we like to look back at the roots of dog sports: flyball, dog agility, dog racing. Who first thought to put pups through their paces? What crazy antics have been relegated to the history books?

Today we take a look at a Dog Derby that used to be held regularly in Upper Michigan.

A Dog Derby: A Winter Sport in Michigan That Thrills the Hearts of the Small Boys

Excerpted from Outing magazine, October 1915.

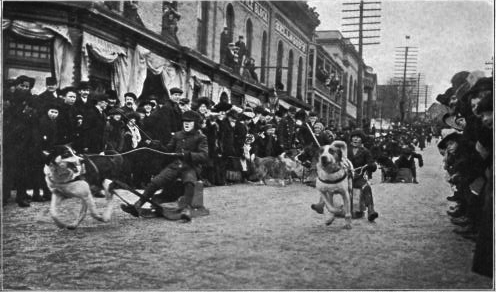

The foremost dog is just turning to tackle, by tooth and nail, an approaching rival.

In the background is seen one of the numerous spills and a case of balk.

By Arthur E. Curtis

During February and March dog racing is one of the winter sports in Upper Michigan. Next to skiing this is always the most popular winter amusement among Michigan’s adopted sons of Scandinavia.

On the day of the contests the city is crowded with eager spectators,—in fact, it is a veritable circus day. Dogs from all the surrounding country are entered in the races and many sets of preliminaries are run off on the race course, which is laid out on one of the main streets of the city. When these are over the crowds adjourn to the big church dinners, after which come the final exciting contests and the awarding of the prizes.

The boys “drive” the dogs with one small rein and a large whip, the latter being the more efficient means of control. It is often a case, in these races, of the hare and the tortoise, for usually two or three of the biggest animals get into a dispute and immediately the other large dogs, who perhaps have a good start in advance, forget the importance of the race and retrace their steps to pitch into the fray—in spite of the violent attempts of their drivers to keep them at the business in hand. It is not unusual to see a dozen or more dogs, boys, harnesses, and sleds in one howling, squirming mix-up.

Thus a little skinny cur, perhaps the slowest in the bunch, who fell far behind at the start, or one that is getting badly worsted in the fray, often pulls away from his more worthy competitors and skips down across the coveted finishing line two blocks away and wins the race. Many dogs and sleds finish in good time, with their drivers missing, which does not count. Frantic drivers hunting for, and capturing their steeds, and clinging to overturned sleds compose one of the chief elements in the exciting and sidesplitting contest.

The dog’s strong love for the society of his fellow-dogs is a matter of common knowledge, and this gregarious instinct plays havoc, at times, with the dog-racing game and prevents it from becoming a universal sport among those classes of society who are well dogged. When a fleet dog has distanced his competitors and suddenly finds that he is alone, he usually stops abruptly and looks around for his friends and rivals, and unless he has a driver who is very skilful and unscrupulous in the use of the whip he will sit down and wait for them. At this the crowd howls with delight. Also a flea bite at a psychological moment has been known to cause a leading cur to stop in order to use one of his hind legs for a bit of energetic scratching, which calls forth a volley of Scandinavian vocabulary from his youthful driver and his elder brother on the side-lines.

Another unique feature of these dog races is the cats. Cats are indispensable, it would seem, for a good dog race. Just as the bull in a bull fight often shows upon entering the arena a disposition to lie gently down in the shade of the wall instead of charging fiercely into the hot sun at the toreadors, so these good-natured Scandinavian dogs, overgrown and awkward, often feel more like stalking peacefully about or lying down on the starting line than entering into the proposed outdoor track meet for the amusement of the vulgar multitude. Like true Scandinavians, however, they are very efficient once their.phlegmatic dispositions are aroused. Evidently something is needed to perform this function.

And cats fill the bill. One sprightly feline of whatever size, shape, color, or breed is worth more in dispelling a dog’s apathy than a five-dollar prize at the end of a racecourse, with all the honor thrown in.

Fully realizing all this, when drivers and steeds are in readiness but enthusiasm runs low, the promoters and coaches cause several starved cats to be liberated from sacks some fifty feet down the course in front of the dogs. Then the excitement begins.

With howls from dogs and crowd, the race is on. The fleeing felines usually keep in the course, for the noisy lines of spectators form a solid wall on either side. Zip! Zip! and pursuers and pursued are over the finish line. The driver, in the meantime, must cling to his sleigh and be on it somehow at the finish, and then use his best efforts to keep his steed from diving into a basement or dashing into an alley in hot pursuit of his victim. Sometimes, on her flight down the race course, a wily feline spies an opening among the legs of the onlookers along the sides. She suddenly veers and darts through, and dogs, sleds, and drivers attempt to follow before the aforesaid legs and their owners know what is happening. A small riot results.

Thus the contests progress until at last, after the strenuous work of the judges is completed, the winners are declared, and the prizes, consisting of money, skis, flour, mittens, etc., are presented without further formality.

A special race is held in which the boys stand on six-foot skis and are drawn by the dogs. This is a very difficult feat for the youngsters and many a spill results. It is considered by the Norwegians, the greatest skiers, as a valuable training for ski jumping.

Leave a comment